Sonnet 130 by William Shakespeare mocks and criticizes the petrarchan love sonnet tradition. Noted as one of the dark lady sonnets, it is a parody of the traditional sonnet form in that it is written in praise not of the object of love but of the speaker’s clear-eyed acceptance of the flaws of both love and the beloved. Generally speaking, traditional petrarchan sonnets attempt to make the beloved ideal, emphasizing their beauty and greatness. In contrast, Sonnet 130 celebrates the real rather than imaginative aspects of love.

Sonnet 130 differs from traditional sonnets in that it emphasizes the woman’s flaws rather than her beauty. The speaker acknowledges from the outset that his beloved is not a traditional beauty, calling her “nothing like the sun”. This is a challenge of the traditional sonnet form in which the beauty of the woman is exalted. Additionally, the poem goes on to list her physical and other flaws. For example, her eyes are not “like the sun” her lips are not “red,” her hairs are like wires, her breath not sweet, she is “so different” from others beauty, and her cheeks are not “rosy.” By doing so, the poem implies that the speaker’s love is not based on outward beauty but rather on a much more essential quality such as kindness, intelligence or inner beauty.

In addition to its challenge of beauty ideals, Sonnet 130 also critiques the concept of idealizing the beloved in comparison to nature or things of beauty— a concept closely associated with petrarchan conventions. The speaker delights in the difference between his beloved and things of beauty, rejecting the traditional comparison between beloved and rose, snow, coral, or stars. By challenging the traditional comparison between object of love and beauty, the poem breaks with petrarchan conventions, mocking the idealized beauty of petrarchan sonnets.

Furthermore, the form of Sonnet 130 mocks the traditional form of the petrarchan sonnet. This sonnet is composed of three quatrains and a couplet, as opposed to the traditional form of two quatrains and two couplets. Moreover, the poem uses iambic pentameter, but does not adhere strictly to the traditional Petrarchan metrical structure. Variations in the meter occur total of 4 times when three unstressed syllables (as opposed to the traditional two) follow at the beginning of the line. For example, in the second line, the unstressed syllables of “compares” are followed by another syllable. Add to this its numerous rhymes, and the poem moves away from the traditional style.

Variety of Themes

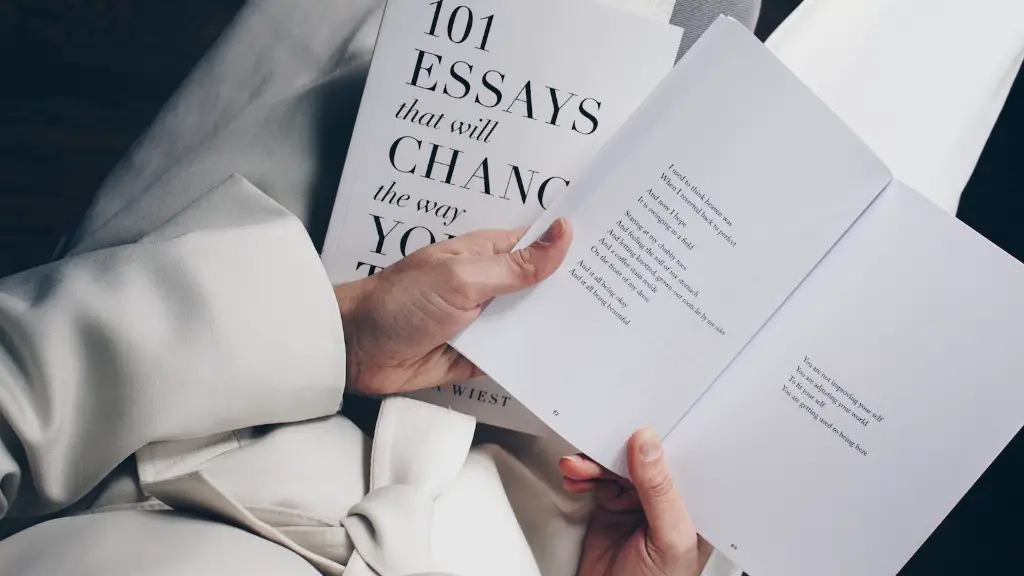

Not only does Sonnet 130 mock the traditional sonnet form, but it also introduces a new type of theme. Traditional sonnets often deal with themes of idealized love, beauty, and the artist’s struggle with their own mortality. Sonnet 130, in contrast, focuses on the reality of the relationship and offers a more human, realistic view of love. This is seen through the contrast between the traditional comparisons between object of love and natural beauty and the speaker’s criticism of his beloved as “ashen”, “so different”, and “unlike the sun.” By setting his beloved apart from traditional descriptions, the speaker emphasizes the beloved’s uniqueness and humanity.

Moreover, the poem looks beyond the beauty of the beloved to the love the speaker has for her. The speaker does not love her for her physical attributes—he loves her for her “kind” nature, for her ability to make him laugh, for their shared understanding, and for the amusement she brings him. Even the poem’s physical visualizations of her—eyes “not like the sun” and her “ashen” complexion—are developed due to her natural beauty and her differences from the traditional beauty ideals. These differences, too, become points of love, emphasizing how their love is unique and special.

An Honest Perspective

The speaker in Sonnet 130 does not attempt to idealize the beloved or make her seem holier than she is; instead, he presents a completely honest perspective about the woman he loves. He does not idealize her beauty or her character—he acknowledges her flaws and praises her for the qualities she does have. This type of honest perspective is rare in traditional sonnets which often portray their beloveds in romanticized or idealized ways. Sonnet 130 presents a challenge to this standard and offers an unflinching, honest look at both himself and his beloved.

In conclusion, Sonnet 130 mocks and criticizes the petrarchan love sonnet tradition. Through its challenge of beauty ideals, its critique of the comparison between object of love and beauty, its challenge of traditional forms, and its new themes, the poem redefines relationships and love in general by introducing an honest perspective of both the speaker and the beloved.

Distrust of Beauty

Apart from the speaker’s honest perspective of the beloved, the poem also hints at a distrust of beauty itself. The speaker does not dismiss the beloved’s beauty completely but he does emphasize physical flaws and other qualities. By doing this, the poem implies that he does not believe beauty can exist without flaws and that physical beauty can be deceiving. This distrust of beauty is not often seen in traditional, idealistic sonnets and represents yet another challenge to petrarchan love sonnet tradition.

The poem also links beauty to deception in the comparison between the beloved and the sun. By stating that her eyes are not like the sun, the speaker implies that a visual comparison between the beloved and the sun is deceiving and that one should look beyond beauty to discover more essential qualities of the beloved. This implies that the beloved is more than her appearance and that her beauty is not her only attractive quality.

Moreover, the poem also makes a link between deception and the traditional petrarchan comparison between object of love and natural beauty. The traditional comparison often plays on physical beauty and tries to elevate the beloved to a higher, Platonic level of beauty. The speaker in Sonnet 130, however, rejects this comparison, suggesting that the traditional comparisons are deceiving and cannot capture the truth of the beloved’s character and beauty. By doing so, the poem implies that beauty can be deceiving and a superficial measure of the beloved’s virtues.

Uniqueness of Love

In addition to its mistrust of beauty, the poem celebrates the unique, sometimes unconventional aspects of love. The speaker does not love his beloved for her beauty or other outward qualities; instead, he loves her for her kindness, her ability to make him laugh, their shared understanding, and the amusement she brings him. These qualities suggest that love can exist beyond beauty and that it is deeper and more complex than simply being attracted to a beautiful person.

Moreover, the poem uses variations in the meter of the poem—unstressed syllables at the beginning of the line, unusual rhymes, etc.—to suggest that the speaker’s love is unique and should not conform to traditional standards and conventions. The poem suggests that the speaker’s love is not necessarily the same as “traditional” love; instead, it is its own form and should embrace one’s uniqueness in love.

The poem also makes its point with powerful metaphors. For example, the beloved’s “breath” is described as being “as sweetas silent thought/In the noon day” suggesting that her breath is pure and has a silent but powerful effect. This metaphor implies that the speaker loves the beloved for qualities beyond physical beauty—such as her power to inspire him and her ability to quiet him with her thoughtfulness.

Subjectivity of Love

In the same vein, the poem emphasizes the subjectivity of love. This is seen not only in the speaker’s refusal to uphold traditional beauty standards, but also in his understanding that each person is loved in their own unique way. For example, the speaker emphasizes that he alone feels the beloved’s “true worth,” implying that love is subjective and that only he can truly appreciate the beloved.

Furthermore, the poem celebrates both the uniqueness of love and its subjectivity. By doing so, it implies that love does not have to conform to traditional standards and expectations and that it can exist in its own unique form. By presenting an honest perspective of both the speaker and the beloved, the poem redefines relationships, suggesting that beauty and love can coexist and that it is not necessary to idealize the beloved in order to love her.

Use of Humor

Finally, the poem uses humor to challenge the traditional petrarchan sonnet form and to satirize the concept of idealizing the beloved. The poem playfully enumerates the flaws of the beloved, humorously challenging the traditional idealization of her beauty. By doing this, the poem not only mocks the traditional form, but also challenges the idea that one must idealize their beloved in order to love them. This challenges traditional beliefs and encourages readers to look beyond beauty and accept the unique strengths and weaknesses of the person they love.

Moreover, the poem uses understatement to mock the idea of idealizing the beloved. For example, the line “I love to hear her speak, yet well I know/That music hath a far more pleasing sound”, ironically emphasizes the speaker’s preference for his beloved’s speech over the music, in spite of her “less than beautiful” qualities. This subtle humor also conveys the speaker’s love for the beloved and suggest that it is possible to find beauty in something that is not traditionally regarded as beautiful.

In conclusion, Sonnet 130 mocks and critiques the petrarchan love sonnet tradition. The poem challenges beauty ideals and the comparison between object of love and beauty, the traditional form and the introduction of new themes, and the conventional idealized representation of the beloved. Furthermore, the poem celebrates the unique aspects of love and implies a distrust of beauty and that beauty can be deceiving. The poem also uses humor to mock the traditional love sonnet form and to challenge the idealization of the beloved, implying that it is possible to find beauty in non-traditional places.